Superb Maori Treasure Box “Waka Huia”

Maori people, Poverty Bay, New Zealand

Circa 1840

Carved by notable Maori leader and master carver Raharuhi Rukupo

Wood, hematite ocher, paua shell

Length 22 1/2 inches

Provenance: Major General Horatio Gordon Robley, collected 1864-1866 / sold by Robley in 1902 to the Königlich Zoologisches, Anthropologisch-Ethnographisches Museum, later the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Dresden, collection number 13.812 / Everett Rassiga, Bern / Sotheby’s New York, December 2nd 1983 / Morris Pinto, New York, 1985/86 / Joe and Barbara Abensur, London, 2005 / Jean-Baptiste Bacquart, Paris 2013

Art Loss Register certificate provided #S00250490

For the Maori people of New Zealand, personal ornaments were regarded as precious and powerful objects. Worn primarily to accentuate the beauty of the head and neck, these sacred ornaments included pendants of green nephrite and whale ivory, ornamental combs of bone and wood, and white-tipped black feathers of the now extinct huia bird that served as hair decoration emblematic of high rank. Intimately associated with the head, the most sacred region of the body, these ornaments absorbed the mana, or potent supernatural force, of their wearers and were handled and stored with great care when not in use. To safely contain these personal ornaments, skilled Maori carvers, tohunga whakairo, fashioned ornately carved treasure boxes called waka huia, or literally “feather canoe”. Imbued with the owner’s mana, these exquisitely carved boxes were regarded as treasures in their own right and they were often given individual names and could be presented as gifts during significant social events and tribal alliances. Treasure boxes were designed to be suspended from the low hanging rafters of a Maori home to ensure the boxes’ supernaturally powerful contents remained safely out of reach. Secured by two cords bound to the pommels at each end, the boxes visibly hung above the heads of the owner and his family, and as they were most often viewed from below, the undersides were often elaborately carved with the same care and attention given to their upper surfaces.

Carved by the notable Maori leader and renowned master carver Raharuhi Rukupo around 1840, the treasure box presented here is perhaps the finest of its type, exceptional both for its powerful figurative forms and exquisitely carved curvilinear ornamentation. The pair of large, sinuously carved female tiki figures project prominently from each end of the box; their elegantly arched bodies fashioned to peer downwards with a watchful eye on the residents below. Rendered within the arms of the large tiki figures are four mythological manaia figures, traditionally believed to be the messengers between the earthly world of mortals and the domain of the spirits. Incorporated into carvings, they were intended as apotropaic motifs, helping to guard against evil spirits. Notched circular inlays of iridescent paua shell further highlight the eyes of the tiki and manaia figures. The entire surface of the treasure box is lavishly carved with raised reliefs, including double spirals, called koru, evoking the newly unfurling frond from the silver fern. Parallel rows of finely carved raised reliefs adorn much of the remaining surface. Referred to as rauponga, they serve as stylized representations of the intricate patterns found on the leaves of the giant tree fern, or ponga. Like other Maori objects regarded as taonga, or treasures, the box was painted with an application of kokowai, a traditional mixture of red hematite ocher and shark liver oil, giving the surface a rich and lustrous finish; the patina further deepened by the routine handling of its chiefly owner, before being acquired by General Horatio Gordon Robley in 1864-66.

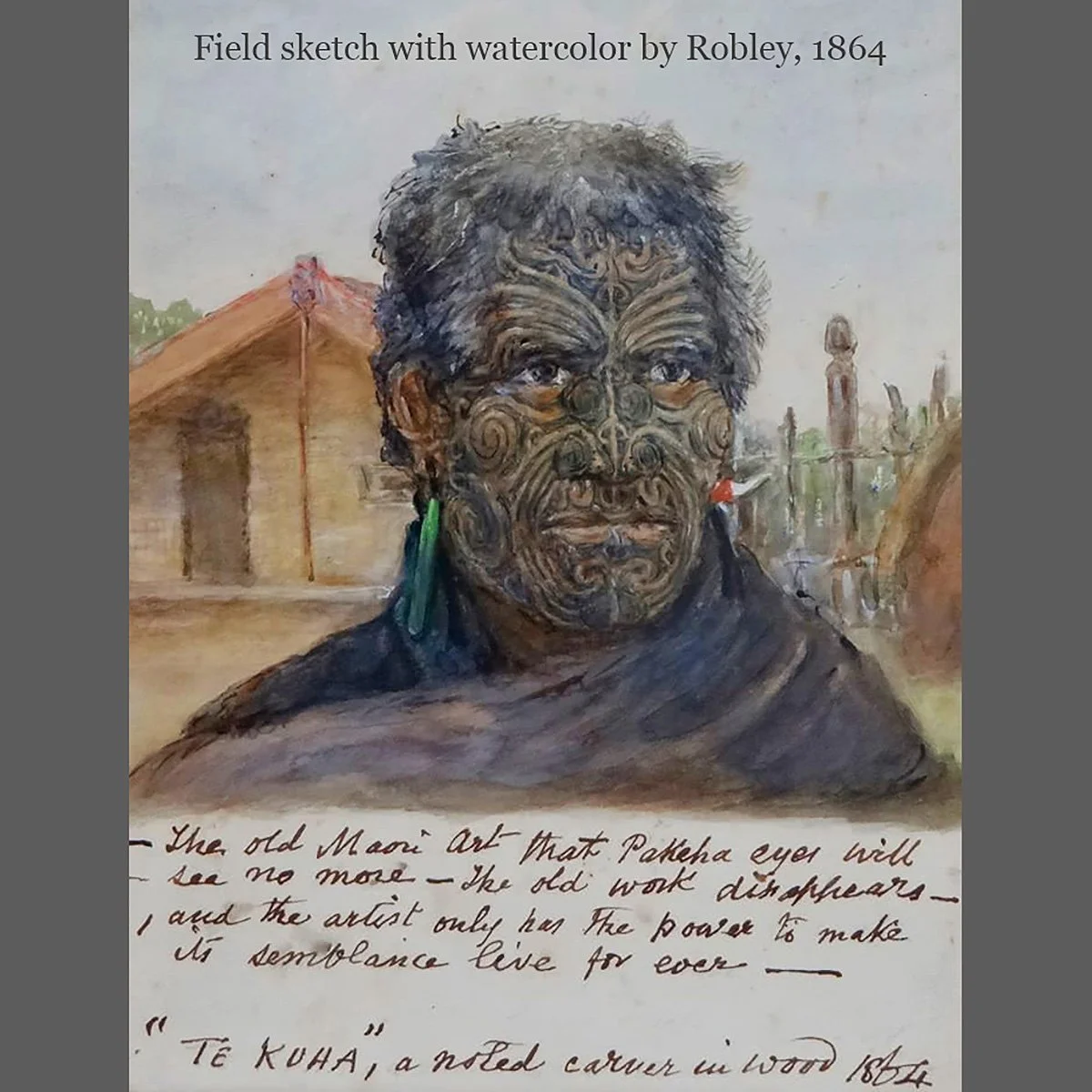

An important yet enigmatic figure in British history, General Robley was known not only for his distinguished service during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860’s, but also his passion for ethnology. In April of 1864, Robley led his troops to Tauranga, near the Bay of Plenty, to join General Cameron’s forces attacking Gate Pa. Here Robley remained for nineteen months, during which time his important series of sketches of Maori life were produced. A gifted illustrator and painter, Robley was particularly captivated by the elaborately carved patterns displayed in Maori carvings and by the intricate facial tattoos, known as moko, worn by the Maori people. Though he continued to passionately acquire Maori objects for his collection after his return to England in June of 1866, it’s likely that Robley acquired the treasure box directly from Rukupo. Both men were distinguished leaders and representatives of their people and were directly engaged in the negotiations between the British government and the Maori tribes of the region. Rukupo, in 1865, led a delegation of local Maori leaders to seek peace with the British government, offering to take the oath of allegiance, and pledging that two hundred seventy Maori men from his district would surrender. General Robley maintained a deep admiration and keen sensitivity for the Maori people, and following Maori custom, the treasure box would have been presented to him by Rukupo as a symbol of their new alliance.

The New Zealand government described Raharuhi Rukupo as “one of the greatest tohunga whakairo, or expert Maori carvers, of the 19th century”. This remarkable treasure box that he carved and cared for embodies the rare convergence of artistic masterpiece and history that speaks so powerfully to us, across two centuries, from another time and another place, revealing to us another way of being human.

Maori people, Poverty Bay, New Zealand

Circa 1840

Carved by notable Maori leader and master carver Raharuhi Rukupo

Wood, hematite ocher, paua shell

Length 22 1/2 inches

Provenance: Major General Horatio Gordon Robley, collected 1864-1866 / sold by Robley in 1902 to the Königlich Zoologisches, Anthropologisch-Ethnographisches Museum, later the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Dresden, collection number 13.812 / Everett Rassiga, Bern / Sotheby’s New York, December 2nd 1983 / Morris Pinto, New York, 1985/86 / Joe and Barbara Abensur, London, 2005 / Jean-Baptiste Bacquart, Paris 2013

Art Loss Register certificate provided #S00250490

For the Maori people of New Zealand, personal ornaments were regarded as precious and powerful objects. Worn primarily to accentuate the beauty of the head and neck, these sacred ornaments included pendants of green nephrite and whale ivory, ornamental combs of bone and wood, and white-tipped black feathers of the now extinct huia bird that served as hair decoration emblematic of high rank. Intimately associated with the head, the most sacred region of the body, these ornaments absorbed the mana, or potent supernatural force, of their wearers and were handled and stored with great care when not in use. To safely contain these personal ornaments, skilled Maori carvers, tohunga whakairo, fashioned ornately carved treasure boxes called waka huia, or literally “feather canoe”. Imbued with the owner’s mana, these exquisitely carved boxes were regarded as treasures in their own right and they were often given individual names and could be presented as gifts during significant social events and tribal alliances. Treasure boxes were designed to be suspended from the low hanging rafters of a Maori home to ensure the boxes’ supernaturally powerful contents remained safely out of reach. Secured by two cords bound to the pommels at each end, the boxes visibly hung above the heads of the owner and his family, and as they were most often viewed from below, the undersides were often elaborately carved with the same care and attention given to their upper surfaces.

Carved by the notable Maori leader and renowned master carver Raharuhi Rukupo around 1840, the treasure box presented here is perhaps the finest of its type, exceptional both for its powerful figurative forms and exquisitely carved curvilinear ornamentation. The pair of large, sinuously carved female tiki figures project prominently from each end of the box; their elegantly arched bodies fashioned to peer downwards with a watchful eye on the residents below. Rendered within the arms of the large tiki figures are four mythological manaia figures, traditionally believed to be the messengers between the earthly world of mortals and the domain of the spirits. Incorporated into carvings, they were intended as apotropaic motifs, helping to guard against evil spirits. Notched circular inlays of iridescent paua shell further highlight the eyes of the tiki and manaia figures. The entire surface of the treasure box is lavishly carved with raised reliefs, including double spirals, called koru, evoking the newly unfurling frond from the silver fern. Parallel rows of finely carved raised reliefs adorn much of the remaining surface. Referred to as rauponga, they serve as stylized representations of the intricate patterns found on the leaves of the giant tree fern, or ponga. Like other Maori objects regarded as taonga, or treasures, the box was painted with an application of kokowai, a traditional mixture of red hematite ocher and shark liver oil, giving the surface a rich and lustrous finish; the patina further deepened by the routine handling of its chiefly owner, before being acquired by General Horatio Gordon Robley in 1864-66.

An important yet enigmatic figure in British history, General Robley was known not only for his distinguished service during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860’s, but also his passion for ethnology. In April of 1864, Robley led his troops to Tauranga, near the Bay of Plenty, to join General Cameron’s forces attacking Gate Pa. Here Robley remained for nineteen months, during which time his important series of sketches of Maori life were produced. A gifted illustrator and painter, Robley was particularly captivated by the elaborately carved patterns displayed in Maori carvings and by the intricate facial tattoos, known as moko, worn by the Maori people. Though he continued to passionately acquire Maori objects for his collection after his return to England in June of 1866, it’s likely that Robley acquired the treasure box directly from Rukupo. Both men were distinguished leaders and representatives of their people and were directly engaged in the negotiations between the British government and the Maori tribes of the region. Rukupo, in 1865, led a delegation of local Maori leaders to seek peace with the British government, offering to take the oath of allegiance, and pledging that two hundred seventy Maori men from his district would surrender. General Robley maintained a deep admiration and keen sensitivity for the Maori people, and following Maori custom, the treasure box would have been presented to him by Rukupo as a symbol of their new alliance.

The New Zealand government described Raharuhi Rukupo as “one of the greatest tohunga whakairo, or expert Maori carvers, of the 19th century”. This remarkable treasure box that he carved and cared for embodies the rare convergence of artistic masterpiece and history that speaks so powerfully to us, across two centuries, from another time and another place, revealing to us another way of being human.

Maori people, Poverty Bay, New Zealand

Circa 1840

Carved by notable Maori leader and master carver Raharuhi Rukupo

Wood, hematite ocher, paua shell

Length 22 1/2 inches

Provenance: Major General Horatio Gordon Robley, collected 1864-1866 / sold by Robley in 1902 to the Königlich Zoologisches, Anthropologisch-Ethnographisches Museum, later the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Dresden, collection number 13.812 / Everett Rassiga, Bern / Sotheby’s New York, December 2nd 1983 / Morris Pinto, New York, 1985/86 / Joe and Barbara Abensur, London, 2005 / Jean-Baptiste Bacquart, Paris 2013

Art Loss Register certificate provided #S00250490

For the Maori people of New Zealand, personal ornaments were regarded as precious and powerful objects. Worn primarily to accentuate the beauty of the head and neck, these sacred ornaments included pendants of green nephrite and whale ivory, ornamental combs of bone and wood, and white-tipped black feathers of the now extinct huia bird that served as hair decoration emblematic of high rank. Intimately associated with the head, the most sacred region of the body, these ornaments absorbed the mana, or potent supernatural force, of their wearers and were handled and stored with great care when not in use. To safely contain these personal ornaments, skilled Maori carvers, tohunga whakairo, fashioned ornately carved treasure boxes called waka huia, or literally “feather canoe”. Imbued with the owner’s mana, these exquisitely carved boxes were regarded as treasures in their own right and they were often given individual names and could be presented as gifts during significant social events and tribal alliances. Treasure boxes were designed to be suspended from the low hanging rafters of a Maori home to ensure the boxes’ supernaturally powerful contents remained safely out of reach. Secured by two cords bound to the pommels at each end, the boxes visibly hung above the heads of the owner and his family, and as they were most often viewed from below, the undersides were often elaborately carved with the same care and attention given to their upper surfaces.

Carved by the notable Maori leader and renowned master carver Raharuhi Rukupo around 1840, the treasure box presented here is perhaps the finest of its type, exceptional both for its powerful figurative forms and exquisitely carved curvilinear ornamentation. The pair of large, sinuously carved female tiki figures project prominently from each end of the box; their elegantly arched bodies fashioned to peer downwards with a watchful eye on the residents below. Rendered within the arms of the large tiki figures are four mythological manaia figures, traditionally believed to be the messengers between the earthly world of mortals and the domain of the spirits. Incorporated into carvings, they were intended as apotropaic motifs, helping to guard against evil spirits. Notched circular inlays of iridescent paua shell further highlight the eyes of the tiki and manaia figures. The entire surface of the treasure box is lavishly carved with raised reliefs, including double spirals, called koru, evoking the newly unfurling frond from the silver fern. Parallel rows of finely carved raised reliefs adorn much of the remaining surface. Referred to as rauponga, they serve as stylized representations of the intricate patterns found on the leaves of the giant tree fern, or ponga. Like other Maori objects regarded as taonga, or treasures, the box was painted with an application of kokowai, a traditional mixture of red hematite ocher and shark liver oil, giving the surface a rich and lustrous finish; the patina further deepened by the routine handling of its chiefly owner, before being acquired by General Horatio Gordon Robley in 1864-66.

An important yet enigmatic figure in British history, General Robley was known not only for his distinguished service during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860’s, but also his passion for ethnology. In April of 1864, Robley led his troops to Tauranga, near the Bay of Plenty, to join General Cameron’s forces attacking Gate Pa. Here Robley remained for nineteen months, during which time his important series of sketches of Maori life were produced. A gifted illustrator and painter, Robley was particularly captivated by the elaborately carved patterns displayed in Maori carvings and by the intricate facial tattoos, known as moko, worn by the Maori people. Though he continued to passionately acquire Maori objects for his collection after his return to England in June of 1866, it’s likely that Robley acquired the treasure box directly from Rukupo. Both men were distinguished leaders and representatives of their people and were directly engaged in the negotiations between the British government and the Maori tribes of the region. Rukupo, in 1865, led a delegation of local Maori leaders to seek peace with the British government, offering to take the oath of allegiance, and pledging that two hundred seventy Maori men from his district would surrender. General Robley maintained a deep admiration and keen sensitivity for the Maori people, and following Maori custom, the treasure box would have been presented to him by Rukupo as a symbol of their new alliance.

The New Zealand government described Raharuhi Rukupo as “one of the greatest tohunga whakairo, or expert Maori carvers, of the 19th century”. This remarkable treasure box that he carved and cared for embodies the rare convergence of artistic masterpiece and history that speaks so powerfully to us, across two centuries, from another time and another place, revealing to us another way of being human.