Important Tlatilco Dual-Faced Pretty Lady Figurine - SOLD

Lake Texcoco – now extinct, Western Valley, Central Mexico

Terracotta ceramic, traces of cinnabar and hematite

Height: 4 inches (10 cm)

1300 BCE to 700 BCE

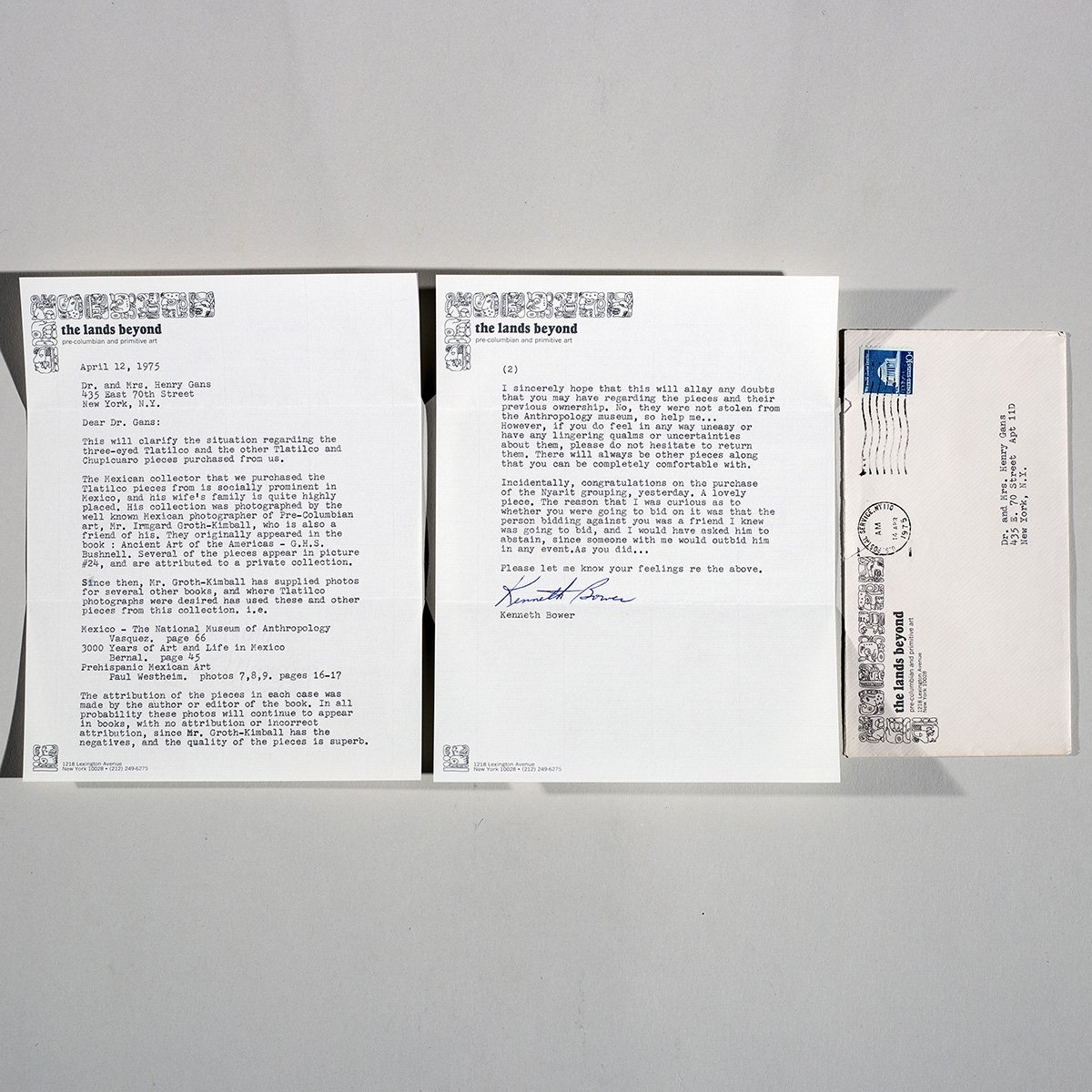

Provenance: Miguel Covarrubias, Mexico City – 1930’s-1940’s

The Lands Beyond Gallery, NY, New York - 1975 and before

Dr. Henry Gans, Fargo, North Dakota - acquired 1975

Joey Martinez, San Diego, CA - acquired July 2020

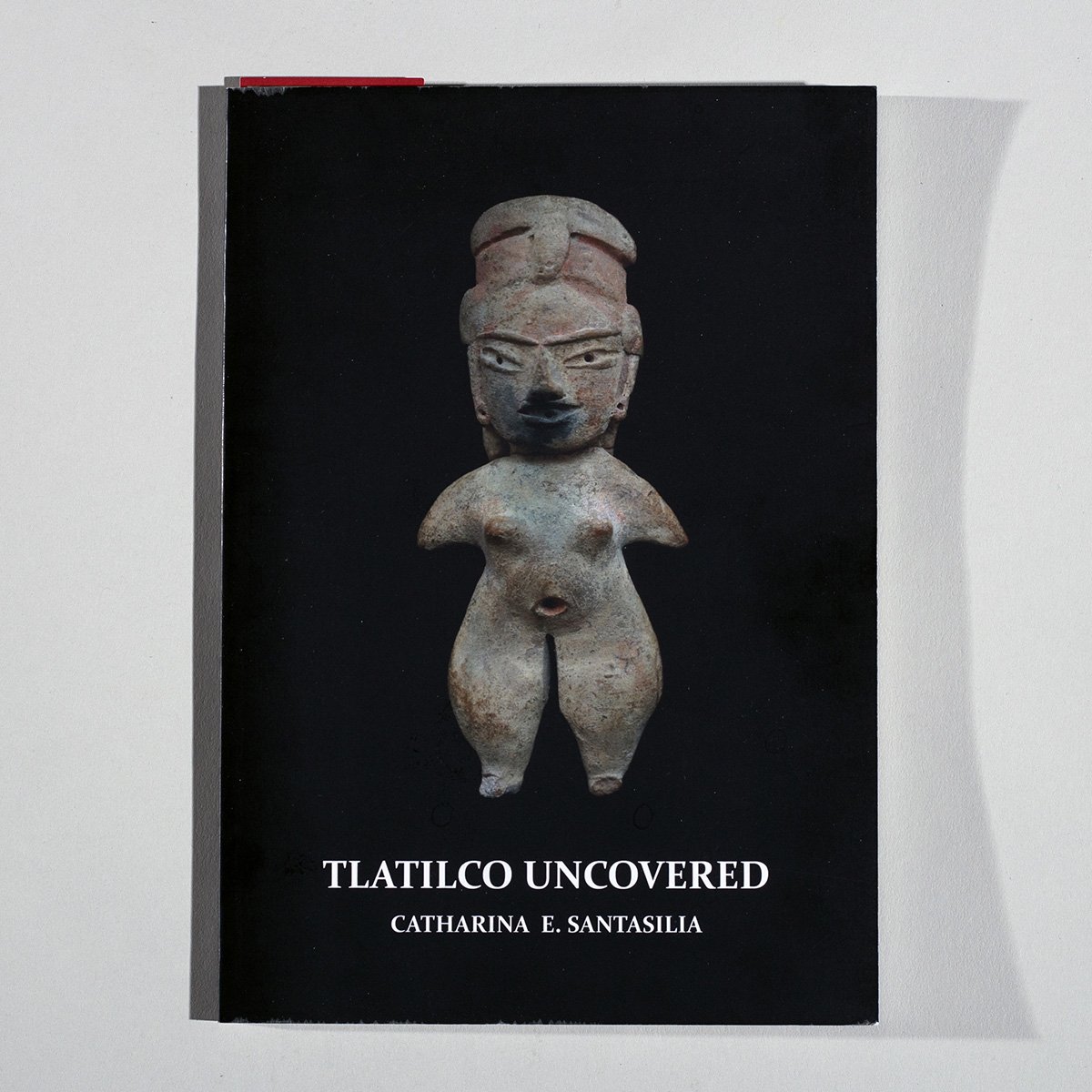

Published: Indian Art of Mexico and Central America, Miguel Covarrubias, Alfred A. Knopf 1957 / Prehispanic Mexican Art, G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1972 / Tlatilco Uncovered, Catharina E. Santasilla, Riverside Museum Press 2018.

Exhibited: Riverside Museum of Art, California. February 3rd - December 30th, 2018.

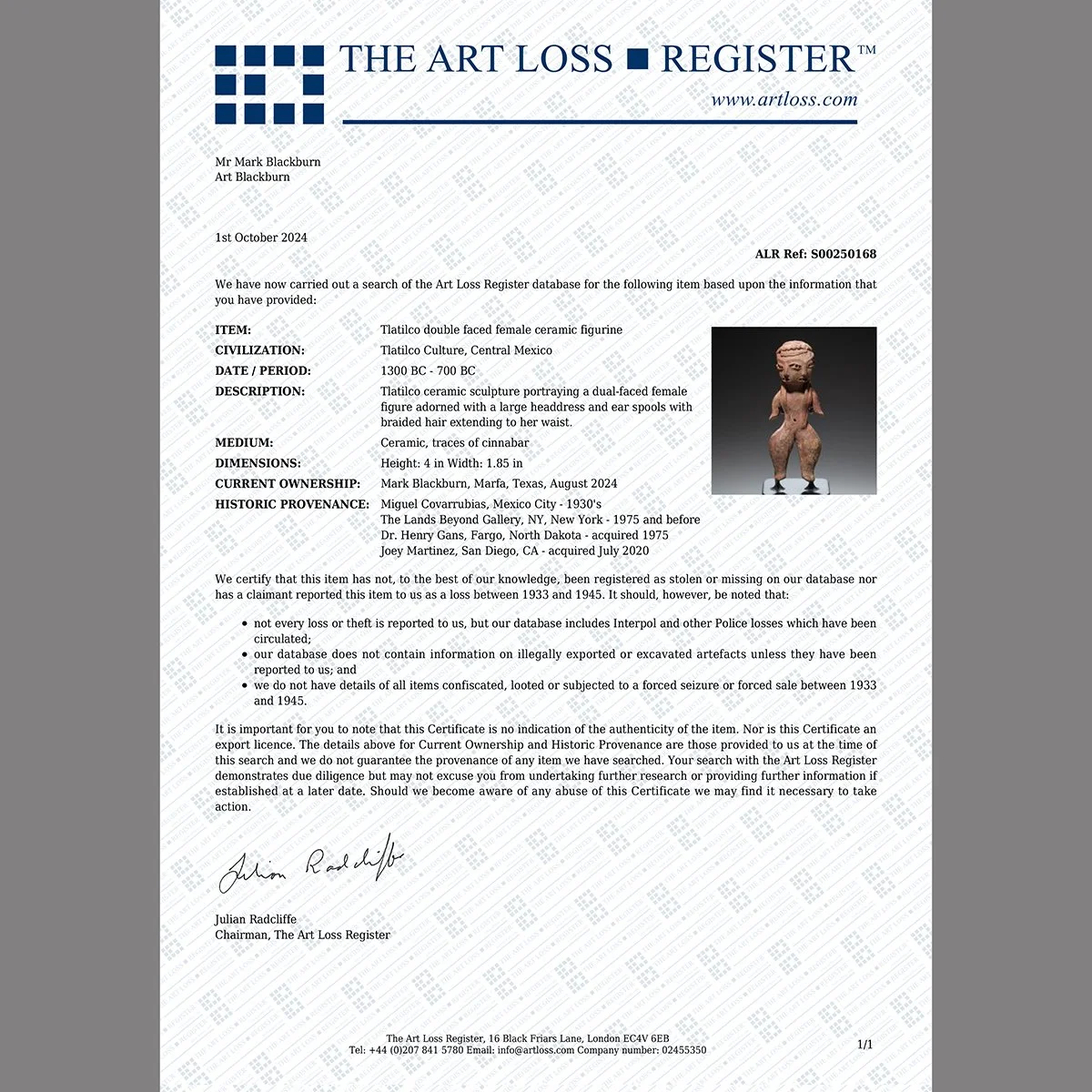

Art Loss Register certificate provided #S00250168

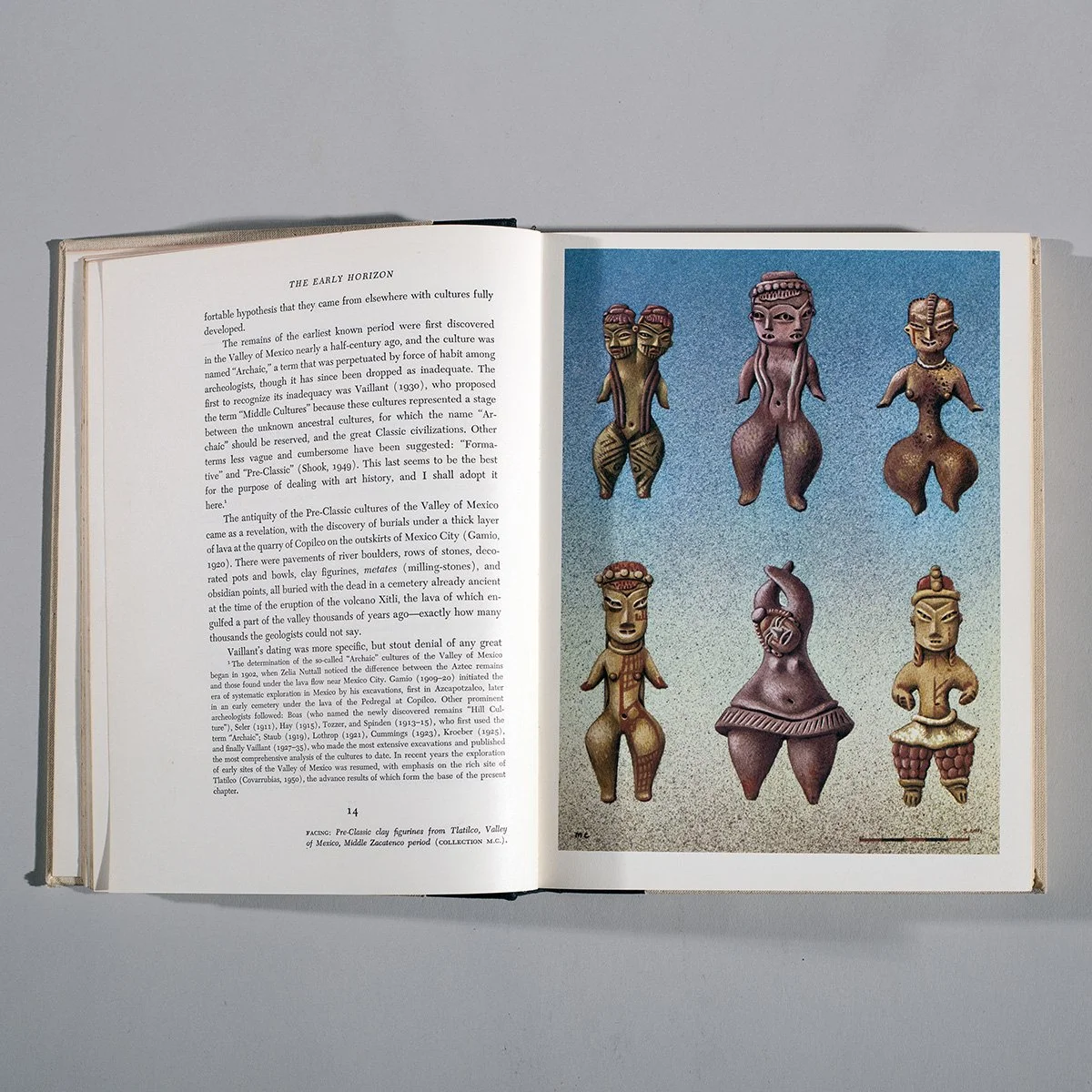

Sculpted some three millennia ago, this remarkable figurine belongs to a group of ceramic effigies known collectively as the Tlatilco “pretty ladies”. Representing some of the earliest ceramic figures produced in Mesoamerica, these small female figurines were made by the Tlatilcans, a pre-Columbian people who lived in a community of three large farming villages along the shores of the now extinct Lake Texcoco, near what is today Mexico City. Since archaeologists in the 1940’s first began excavating the area once inhabited by the Tlatilcans, hundreds of these ceramic figures have been found in what were once village burial sites. Made exclusively by hand without the use of molds and demonstrating a mastery of clay pinching and intricate shaping techniques, the pretty lady figurines were characteristically portrayed nude and served as stylized embodiments of an idealized feminine form. They reveal a dramatic contrast in proportions with an emphasis on prominent wide hips and spherical upper thighs that narrow to a tightly pinched waist. The attenuated arms are often outstretched in a lively pose that has led to the pretty ladies additional designation as “dancers”. The hands and feet of these figurines were often minimally indicated, though by contrast, the hairstyles were finely modeled with great care and attention to detail, suggesting that hair and its styling were of great importance to the people of Tlatilco, as it was for other communities of the region. The large heads with their finely modeled eyes, nose and mouth were the primary focus of these delicate yet powerful figurines and prompted Tlatilco archeologist Michael Coe to remark that the pretty ladies represented the ultimate refinement in the art of figurine-making in central Mexico and are among the most beautiful objects of their size in all of the New World.

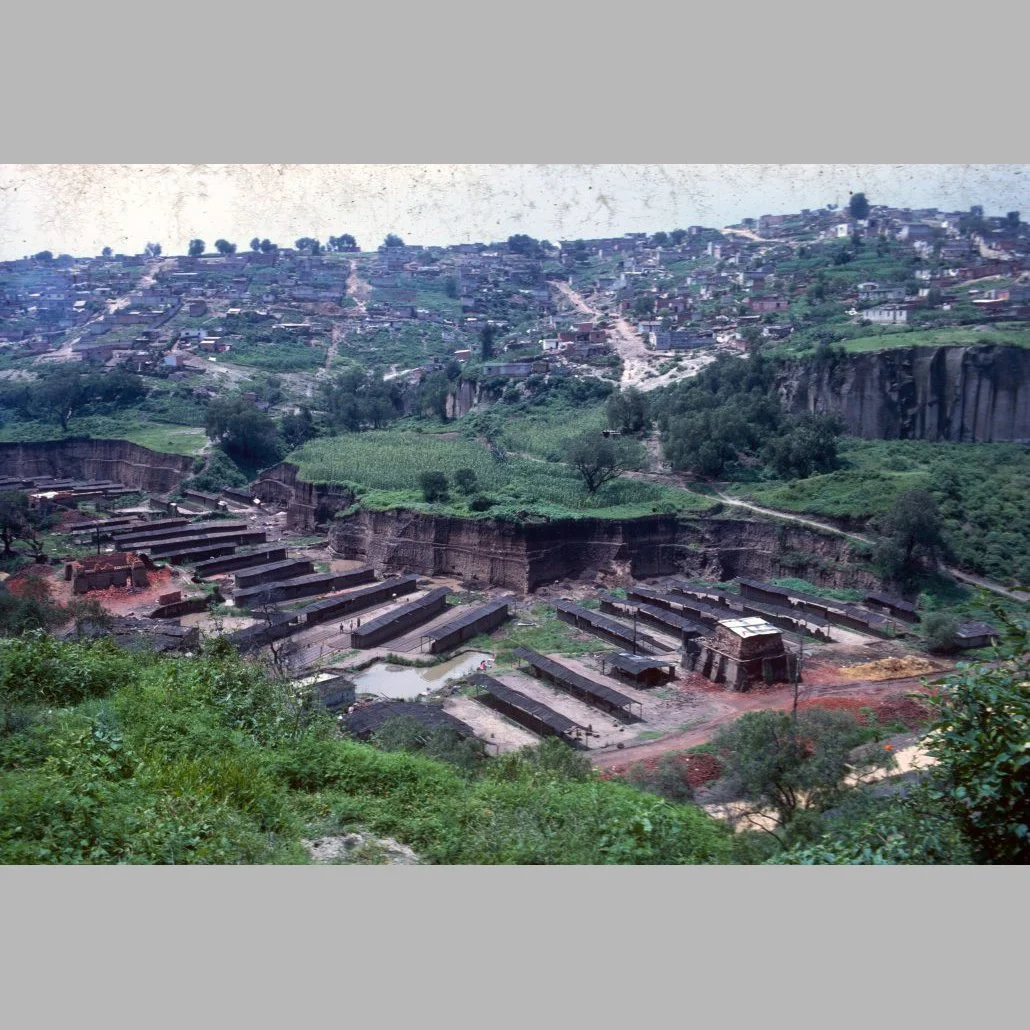

Tlatilco, which is the Nahuatl word for “place of hidden things” emerged from a social landscape of independent farming villages during the Early Formative period, to a more integrated community with control of their surrounding territories, where they cultivated crops such as maize, squash, and chili peppers.Their diet was rich in fish and domesticated deer, rabbits, ducks, and other waterfowl. The climate was more humid than that of today, and the vegetation was much more vibrant, with the fertile soil allowing for a diversity of crops.These ancient fertile fields surrounding Tlatilco had later, during the 20th century, become important sources of clay for brick production utilized in the construction and rapid expansion of the Mexico City’s nearby Federal District. In 1936, the brick makers began unearthing troves of ceramic figurines and polychrome pottery.As word spread of this discovery, art collectors came to the burgeoning outdoor markets to purchase these mysterious ceramic figures.Some of the earliest collectors of these figurines included Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, as well as the renowned artist, art historian, archaeologist, and ethnologist Miguel Covarrubias.

The illustrated writings of Covarrubias reflect his deep interest and profound understanding of the life, customs, and culture of primitive and ancient peoples and gained him great recognition beyond his native Mexico. Led by Covarrubias beginning in 1942, archaeologists began to study the ancient site of Tlatilco in earnest. These federally funded excavations helped to expose hundreds of ancient burials containing not only "pretty lady" figurines but also a corpus of other Tlatilco figurines that encompassed the full gamut of human representation. The excavations uncovered complex burial tableaux featuring large clusters of arranged figurines, suggesting they may have been originally positioned in a standing tableau, including dedicatory portrayals of funeral scenes. The enormous number of durable, finely made objects unearthed at Tlatilco, enabled Covarrubias to establish a more comprehensive typology of Tlatilco ceramic works. Through his comparisons of the local ceramic tradition with that of the contemporary Olmec culture, Covarrubias was able to reveal a large-scale influx of Gulf Coast peoples into the Tlatilco region sometime during the Late Preclassic period, approximately 600 BCE. As a result, scholars now understand that the Tlatilcans were central players in the interregional, multi-ethnic cultural exchange that defined Central Mexican cultural interactions in the following centuries.

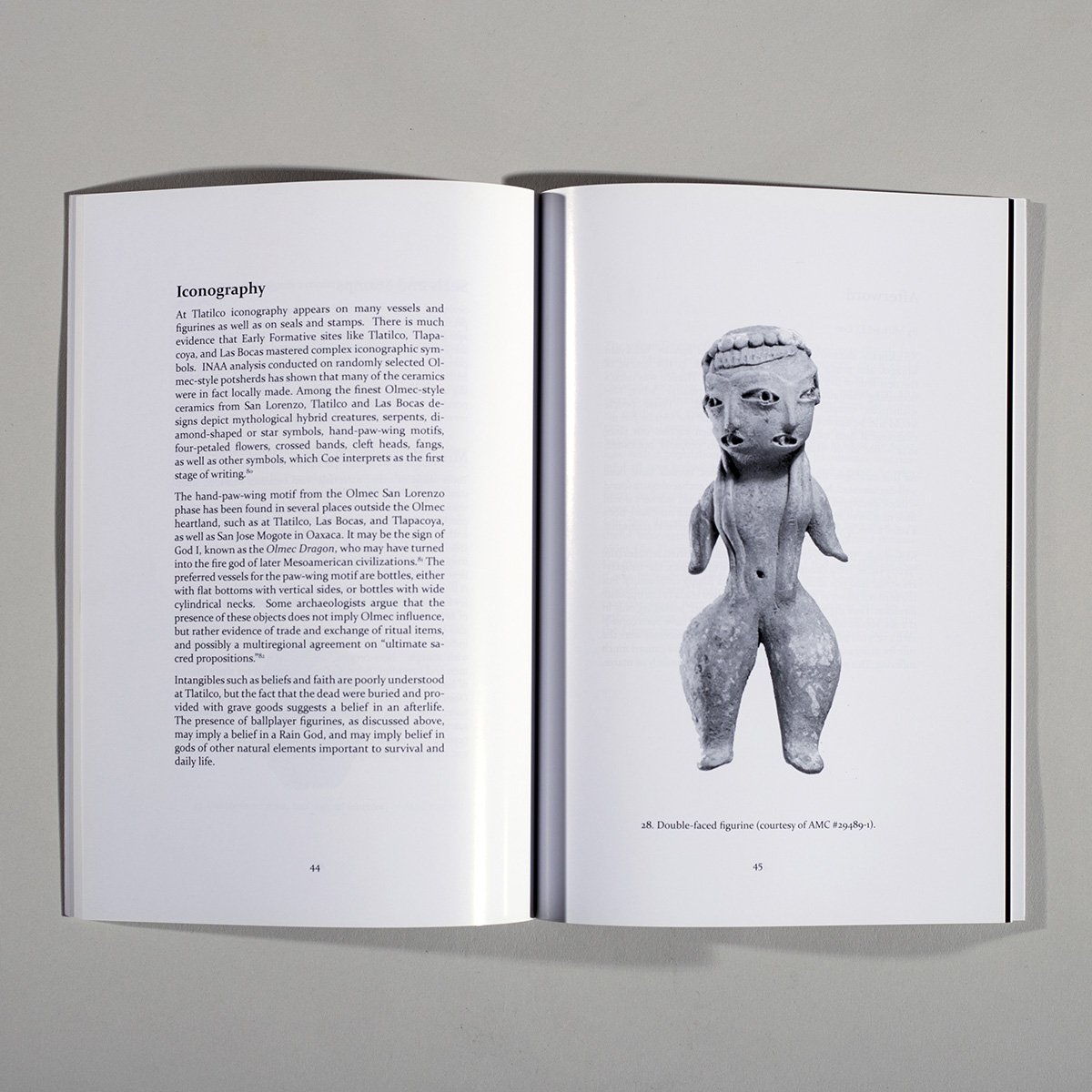

The remarkable pretty lady figurine presented here was recovered by Miguel Covarrubias during his excavations at Tlatilco and was later illustrated in his seminal book “Indian Art of Mexico and Central America” first published in 1957. Of the hundreds of ceramic figurines that were discovered at Tlatilco, only about a dozen recovered to date, share a most intriguing and exceedingly rare feature; dual or bicephalic heads. For decades, art historians had theorized that these rare double-faced figurines represented a dualistic aspect of the Tlatilcan religion. Whether they represented a particular mythical deity or perhaps symbolized broader Mesoamerican concepts of duality was merely speculative. In 2000, a medical historian from the University of Pennsylvania, Gordon Bendersky, came forward with a markedly different and now widely supported theory; that the double-faced figurines of Tlatilco were, in fact, early documentation of a rare condition called diprosopus, a congenital defect resulting in an infant born with a single body but two identical faces fused together. It’s been further proposed that the ancient villages of Lake Texcoco may have been an isolated genetic cluster site for diprosopus, producing those physical features that would have struck Tlatilcans as otherworldly and supernatural. Diprosopus imagery would thus be incorporated into Tlatilcan religion to symbolize duality, a fundamental concept central to Mesoamerican religions.

Covarrubias regarded this rare figurine as one of his most important discoveries at Tlatilco, and he retained it for his personal collection, until later bequeathing it to his wife Rosa. Like other double-faced figurines, the two finely sculpted faces are fused, and together they share a third eye. The figure’s three almond-shaped eyes are wide and narrowed and are delicately modeled in bold relief around small, perforated pupils. Her elevated eyebrow arches are well defined and serve to elegantly integrate the two faces. Like the eyes, the two mouths are depicted in bold relief, with the fine lips framing distinctive cylindrical tongues, and together the eyes and mouths suggest a more fierce animus belying the figurine’s gentle feminine form. The ears are adorned with circular ear spools and her hair is secured with an ornamental headdress, with braided hair extending down to her waist. The shared facial features of the figurine produce a striking and powerful visage, one supernaturally charged with the dualistic forces of good and evil, male and female, day and night, life and death; polarities essential for establishing balance and unity within the Tlatilcan cosmos.

Lake Texcoco – now extinct, Western Valley, Central Mexico

Terracotta ceramic, traces of cinnabar and hematite

Height: 4 inches (10 cm)

1300 BCE to 700 BCE

Provenance: Miguel Covarrubias, Mexico City – 1930’s-1940’s

The Lands Beyond Gallery, NY, New York - 1975 and before

Dr. Henry Gans, Fargo, North Dakota - acquired 1975

Joey Martinez, San Diego, CA - acquired July 2020

Published: Indian Art of Mexico and Central America, Miguel Covarrubias, Alfred A. Knopf 1957 / Prehispanic Mexican Art, G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1972 / Tlatilco Uncovered, Catharina E. Santasilla, Riverside Museum Press 2018.

Exhibited: Riverside Museum of Art, California. February 3rd - December 30th, 2018.

Art Loss Register certificate provided #S00250168

Sculpted some three millennia ago, this remarkable figurine belongs to a group of ceramic effigies known collectively as the Tlatilco “pretty ladies”. Representing some of the earliest ceramic figures produced in Mesoamerica, these small female figurines were made by the Tlatilcans, a pre-Columbian people who lived in a community of three large farming villages along the shores of the now extinct Lake Texcoco, near what is today Mexico City. Since archaeologists in the 1940’s first began excavating the area once inhabited by the Tlatilcans, hundreds of these ceramic figures have been found in what were once village burial sites. Made exclusively by hand without the use of molds and demonstrating a mastery of clay pinching and intricate shaping techniques, the pretty lady figurines were characteristically portrayed nude and served as stylized embodiments of an idealized feminine form. They reveal a dramatic contrast in proportions with an emphasis on prominent wide hips and spherical upper thighs that narrow to a tightly pinched waist. The attenuated arms are often outstretched in a lively pose that has led to the pretty ladies additional designation as “dancers”. The hands and feet of these figurines were often minimally indicated, though by contrast, the hairstyles were finely modeled with great care and attention to detail, suggesting that hair and its styling were of great importance to the people of Tlatilco, as it was for other communities of the region. The large heads with their finely modeled eyes, nose and mouth were the primary focus of these delicate yet powerful figurines and prompted Tlatilco archeologist Michael Coe to remark that the pretty ladies represented the ultimate refinement in the art of figurine-making in central Mexico and are among the most beautiful objects of their size in all of the New World.

Tlatilco, which is the Nahuatl word for “place of hidden things” emerged from a social landscape of independent farming villages during the Early Formative period, to a more integrated community with control of their surrounding territories, where they cultivated crops such as maize, squash, and chili peppers.Their diet was rich in fish and domesticated deer, rabbits, ducks, and other waterfowl. The climate was more humid than that of today, and the vegetation was much more vibrant, with the fertile soil allowing for a diversity of crops.These ancient fertile fields surrounding Tlatilco had later, during the 20th century, become important sources of clay for brick production utilized in the construction and rapid expansion of the Mexico City’s nearby Federal District. In 1936, the brick makers began unearthing troves of ceramic figurines and polychrome pottery.As word spread of this discovery, art collectors came to the burgeoning outdoor markets to purchase these mysterious ceramic figures.Some of the earliest collectors of these figurines included Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, as well as the renowned artist, art historian, archaeologist, and ethnologist Miguel Covarrubias.

The illustrated writings of Covarrubias reflect his deep interest and profound understanding of the life, customs, and culture of primitive and ancient peoples and gained him great recognition beyond his native Mexico. Led by Covarrubias beginning in 1942, archaeologists began to study the ancient site of Tlatilco in earnest. These federally funded excavations helped to expose hundreds of ancient burials containing not only "pretty lady" figurines but also a corpus of other Tlatilco figurines that encompassed the full gamut of human representation. The excavations uncovered complex burial tableaux featuring large clusters of arranged figurines, suggesting they may have been originally positioned in a standing tableau, including dedicatory portrayals of funeral scenes. The enormous number of durable, finely made objects unearthed at Tlatilco, enabled Covarrubias to establish a more comprehensive typology of Tlatilco ceramic works. Through his comparisons of the local ceramic tradition with that of the contemporary Olmec culture, Covarrubias was able to reveal a large-scale influx of Gulf Coast peoples into the Tlatilco region sometime during the Late Preclassic period, approximately 600 BCE. As a result, scholars now understand that the Tlatilcans were central players in the interregional, multi-ethnic cultural exchange that defined Central Mexican cultural interactions in the following centuries.

The remarkable pretty lady figurine presented here was recovered by Miguel Covarrubias during his excavations at Tlatilco and was later illustrated in his seminal book “Indian Art of Mexico and Central America” first published in 1957. Of the hundreds of ceramic figurines that were discovered at Tlatilco, only about a dozen recovered to date, share a most intriguing and exceedingly rare feature; dual or bicephalic heads. For decades, art historians had theorized that these rare double-faced figurines represented a dualistic aspect of the Tlatilcan religion. Whether they represented a particular mythical deity or perhaps symbolized broader Mesoamerican concepts of duality was merely speculative. In 2000, a medical historian from the University of Pennsylvania, Gordon Bendersky, came forward with a markedly different and now widely supported theory; that the double-faced figurines of Tlatilco were, in fact, early documentation of a rare condition called diprosopus, a congenital defect resulting in an infant born with a single body but two identical faces fused together. It’s been further proposed that the ancient villages of Lake Texcoco may have been an isolated genetic cluster site for diprosopus, producing those physical features that would have struck Tlatilcans as otherworldly and supernatural. Diprosopus imagery would thus be incorporated into Tlatilcan religion to symbolize duality, a fundamental concept central to Mesoamerican religions.

Covarrubias regarded this rare figurine as one of his most important discoveries at Tlatilco, and he retained it for his personal collection, until later bequeathing it to his wife Rosa. Like other double-faced figurines, the two finely sculpted faces are fused, and together they share a third eye. The figure’s three almond-shaped eyes are wide and narrowed and are delicately modeled in bold relief around small, perforated pupils. Her elevated eyebrow arches are well defined and serve to elegantly integrate the two faces. Like the eyes, the two mouths are depicted in bold relief, with the fine lips framing distinctive cylindrical tongues, and together the eyes and mouths suggest a more fierce animus belying the figurine’s gentle feminine form. The ears are adorned with circular ear spools and her hair is secured with an ornamental headdress, with braided hair extending down to her waist. The shared facial features of the figurine produce a striking and powerful visage, one supernaturally charged with the dualistic forces of good and evil, male and female, day and night, life and death; polarities essential for establishing balance and unity within the Tlatilcan cosmos.

Lake Texcoco – now extinct, Western Valley, Central Mexico

Terracotta ceramic, traces of cinnabar and hematite

Height: 4 inches (10 cm)

1300 BCE to 700 BCE

Provenance: Miguel Covarrubias, Mexico City – 1930’s-1940’s

The Lands Beyond Gallery, NY, New York - 1975 and before

Dr. Henry Gans, Fargo, North Dakota - acquired 1975

Joey Martinez, San Diego, CA - acquired July 2020

Published: Indian Art of Mexico and Central America, Miguel Covarrubias, Alfred A. Knopf 1957 / Prehispanic Mexican Art, G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1972 / Tlatilco Uncovered, Catharina E. Santasilla, Riverside Museum Press 2018.

Exhibited: Riverside Museum of Art, California. February 3rd - December 30th, 2018.

Art Loss Register certificate provided #S00250168

Sculpted some three millennia ago, this remarkable figurine belongs to a group of ceramic effigies known collectively as the Tlatilco “pretty ladies”. Representing some of the earliest ceramic figures produced in Mesoamerica, these small female figurines were made by the Tlatilcans, a pre-Columbian people who lived in a community of three large farming villages along the shores of the now extinct Lake Texcoco, near what is today Mexico City. Since archaeologists in the 1940’s first began excavating the area once inhabited by the Tlatilcans, hundreds of these ceramic figures have been found in what were once village burial sites. Made exclusively by hand without the use of molds and demonstrating a mastery of clay pinching and intricate shaping techniques, the pretty lady figurines were characteristically portrayed nude and served as stylized embodiments of an idealized feminine form. They reveal a dramatic contrast in proportions with an emphasis on prominent wide hips and spherical upper thighs that narrow to a tightly pinched waist. The attenuated arms are often outstretched in a lively pose that has led to the pretty ladies additional designation as “dancers”. The hands and feet of these figurines were often minimally indicated, though by contrast, the hairstyles were finely modeled with great care and attention to detail, suggesting that hair and its styling were of great importance to the people of Tlatilco, as it was for other communities of the region. The large heads with their finely modeled eyes, nose and mouth were the primary focus of these delicate yet powerful figurines and prompted Tlatilco archeologist Michael Coe to remark that the pretty ladies represented the ultimate refinement in the art of figurine-making in central Mexico and are among the most beautiful objects of their size in all of the New World.

Tlatilco, which is the Nahuatl word for “place of hidden things” emerged from a social landscape of independent farming villages during the Early Formative period, to a more integrated community with control of their surrounding territories, where they cultivated crops such as maize, squash, and chili peppers.Their diet was rich in fish and domesticated deer, rabbits, ducks, and other waterfowl. The climate was more humid than that of today, and the vegetation was much more vibrant, with the fertile soil allowing for a diversity of crops.These ancient fertile fields surrounding Tlatilco had later, during the 20th century, become important sources of clay for brick production utilized in the construction and rapid expansion of the Mexico City’s nearby Federal District. In 1936, the brick makers began unearthing troves of ceramic figurines and polychrome pottery.As word spread of this discovery, art collectors came to the burgeoning outdoor markets to purchase these mysterious ceramic figures.Some of the earliest collectors of these figurines included Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, as well as the renowned artist, art historian, archaeologist, and ethnologist Miguel Covarrubias.

The illustrated writings of Covarrubias reflect his deep interest and profound understanding of the life, customs, and culture of primitive and ancient peoples and gained him great recognition beyond his native Mexico. Led by Covarrubias beginning in 1942, archaeologists began to study the ancient site of Tlatilco in earnest. These federally funded excavations helped to expose hundreds of ancient burials containing not only "pretty lady" figurines but also a corpus of other Tlatilco figurines that encompassed the full gamut of human representation. The excavations uncovered complex burial tableaux featuring large clusters of arranged figurines, suggesting they may have been originally positioned in a standing tableau, including dedicatory portrayals of funeral scenes. The enormous number of durable, finely made objects unearthed at Tlatilco, enabled Covarrubias to establish a more comprehensive typology of Tlatilco ceramic works. Through his comparisons of the local ceramic tradition with that of the contemporary Olmec culture, Covarrubias was able to reveal a large-scale influx of Gulf Coast peoples into the Tlatilco region sometime during the Late Preclassic period, approximately 600 BCE. As a result, scholars now understand that the Tlatilcans were central players in the interregional, multi-ethnic cultural exchange that defined Central Mexican cultural interactions in the following centuries.

The remarkable pretty lady figurine presented here was recovered by Miguel Covarrubias during his excavations at Tlatilco and was later illustrated in his seminal book “Indian Art of Mexico and Central America” first published in 1957. Of the hundreds of ceramic figurines that were discovered at Tlatilco, only about a dozen recovered to date, share a most intriguing and exceedingly rare feature; dual or bicephalic heads. For decades, art historians had theorized that these rare double-faced figurines represented a dualistic aspect of the Tlatilcan religion. Whether they represented a particular mythical deity or perhaps symbolized broader Mesoamerican concepts of duality was merely speculative. In 2000, a medical historian from the University of Pennsylvania, Gordon Bendersky, came forward with a markedly different and now widely supported theory; that the double-faced figurines of Tlatilco were, in fact, early documentation of a rare condition called diprosopus, a congenital defect resulting in an infant born with a single body but two identical faces fused together. It’s been further proposed that the ancient villages of Lake Texcoco may have been an isolated genetic cluster site for diprosopus, producing those physical features that would have struck Tlatilcans as otherworldly and supernatural. Diprosopus imagery would thus be incorporated into Tlatilcan religion to symbolize duality, a fundamental concept central to Mesoamerican religions.

Covarrubias regarded this rare figurine as one of his most important discoveries at Tlatilco, and he retained it for his personal collection, until later bequeathing it to his wife Rosa. Like other double-faced figurines, the two finely sculpted faces are fused, and together they share a third eye. The figure’s three almond-shaped eyes are wide and narrowed and are delicately modeled in bold relief around small, perforated pupils. Her elevated eyebrow arches are well defined and serve to elegantly integrate the two faces. Like the eyes, the two mouths are depicted in bold relief, with the fine lips framing distinctive cylindrical tongues, and together the eyes and mouths suggest a more fierce animus belying the figurine’s gentle feminine form. The ears are adorned with circular ear spools and her hair is secured with an ornamental headdress, with braided hair extending down to her waist. The shared facial features of the figurine produce a striking and powerful visage, one supernaturally charged with the dualistic forces of good and evil, male and female, day and night, life and death; polarities essential for establishing balance and unity within the Tlatilcan cosmos.